Self righteousness in the aid community

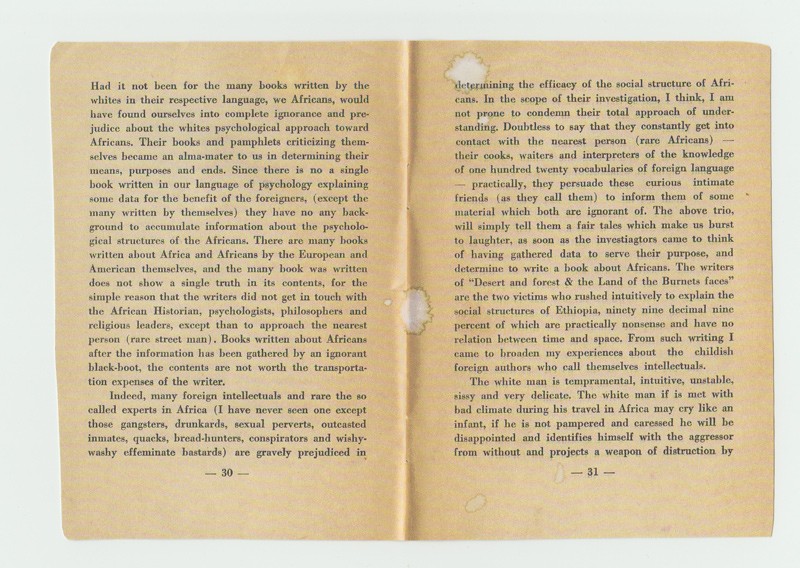

In Professor Mengistu Gedamu’s infamous words, he had never met a group of foreigners who were not a bunch of ‘gangsters, drunkards, sexual perverts, outcasted inmates, quacks, bread hunters, conspirators and wishy-washy effeminate bastards’. Nothing sensitive or politically correct about Mengistu’s sentiments then? The chaplain and I found his academic treatise at the back of the church hall during a long overdue spring clean and the rest of his essay gave us much needed light relief. We imagined ‘The Psychology of the White Races’ to be a rather outdated, minority view point expounded by someone with a rather large chip on his shoulder and an axe to grind. However, it was not long before I was using his piece to regularly illustrate a point, and to help newly arrived ‘forenges’ adapt to their current circumstances. After the euphoria settling into a new culture and experiencing the initial highs it was always hard for newcomers to quite put their finger on the prevailing undercurrent. Ethiopian culture is deep; very deep and goes back millennia. Ethiopians are proud; too proud at times; arrogant and undefeated rather like the British. Their faith in God is strong and fatalism plays a huge part in their lives. And they have little time for patronizing foreigners who have come to teach them this or that and to bring civilization to an already proud nation. Mengistu’s piece was an open window into which forenges could glimpse the darker side, the unspoken viewpoint held by many Ethiopians.

So on my first reading I was amused but I must confess, just a little bit miffed and offended. Mengistu Gedamu had the basis of an argument but had taken it all a little too far. His later supposition was ‘The white man is temperamental, intuitive, unstable, sissy and very delicate. The white man if is met with bad climate during his travel in Africa may cry like an infant’. I thought of such men as Livingston, Stanley, Thesiger, Schweitzer and various other explorers and missionaries whose monumental feats of survival and discovery were legendary and could hardly be described as ‘sissy and delicate’. Deep down I had to admit however the vast majority of foreigners I knew working in the aid world or the foreign and diplomatic service were pretty useless and mirrored fairly closely the description applied by Mengistu. I had already learned the mantra of many of us working abroad that we all fell into one of three types; Missionary, Mercenary or Mad. Conversely, quite a few of my middle class Ethiopian colleagues could quite easily have been similarly classified but definitely not the average farmer, peasant or working man in Ethiopia.

Having established ourselves as an Ethiopian registered company and having progressively ‘gone native’, each time I revisited Mengistu’s essay I found myself increasingly in tune and in agreement with his hypothesis. The number of times I witnessed my Ethiopian colleagues being patronized and treated as inferior beings in subtle, and sometimes less subtle ways - was increasing. Over the years my hearing improved. The nuances of language, prejudice and racism became louder and more audible. Of course ‘Ethiopians should not be paid as much as foreign experts’; how could they know what it was that afflicted them or more importantly how they could escape from their malaise without our help.

Dr Robert Chambers was inspirational in setting out his ‘six biases’ of rural poverty and these ideas are imprinted on my brain in the form of a checklist. A checklist designed to keep us from becoming ‘wishy-washy effeminate bastards’. Without going into a full explanation of Robert Chambers’ ideas he forces us, as aid workers, to go ‘off the road’, into the villages and hills, during the rains, to speak to the dead and disabled, women and children, to stay with them for longer, to give up the pursuit of power and wealth and privilege and to be content with things as they are. His works form the basis of modern philanthropy and underpin the modus operandi of a majority of well-known charitable institutions (despite the fact that most aid workers have never heard of him or his work). However, Chambers himself described the future (in which we now live). He described how research would generate more research and how successful projects would cause visitors, donors, ministers and agency staff to pay attention to ever decreasing ‘tiny atypical islands of activity which attract repeated and mutually re-inforcing attention’. In the end we find once again the ‘blind leading the blind’.

I first observed Naomi at a meeting in UN House – home to the UN peace keeping force in Juba, South Sudan and soldiers from around the world. It was a safe haven for foreign aid workers where it was possible to get a proper plate of fish and chips! At UN House, Internally Displaced People (IDP) had jumped the walls at various points in time, seeking protection from their enemies and then assistance from the international community to meet their physical needs. If Naomi does not mention her status as ‘Humanitarian’ defending the rights and dignity of IDPs and vulnerable individuals at least once in every second sentence, I thought and promised, I would eat my hat! By the end of the meeting I was able to tuck into my fish and chips with no hint of ‘hat’ as a tasteless accompaniment. We felt safe in the knowledge that all IDPs were being protected by Naomi, myself presumably and all our peers sitting round the table. The care and attention lavished upon those unfortunate IDPs and poor Southern Sudanese was sufficient to ensure their safety and mental wellbeing. Our own righteousness was assured and fully evident. Furthermore, the images broadcast through the international media would tell the whole story and consequently ensure sufficient adulation once back home in England.

Three weeks later my local supervisors and I attended another operational meeting to discuss the construction of emergency shelters. They were the experts having spent months building these structures, using the locally available tools, economizing as necessary and negotiating with their fellow IDPs on where they could build and what the constraints might be. Bearing this local knowledge in mind they were asked to leave the meeting while the ‘so called experts in Africa’ determined the best way forward. Mengistu Gedamu’s words sprung immediately to mind once again. ………….